OPINION

If Americans are going to make a dent in reducing carbon emissions — and polling suggests they want to — they are going to have to grapple with the tradeoffs required. An effort in West Texas offers a roadmap for helping people work through the issues.

In West Texas, a team of scientists and outreach professionals brought together private landowners, elected officials, energy companies, community members and others to develop a blueprint for producing energy while preserving the conservation values important to rural communities.

Optimism in West Texas is in short supply these days. But a look back at our recent history of energy booms and busts reveals a lesson in finding opportunity through adversity – and a possible path forward through difficult times.

The United Nations (UN) launched the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development to address an ongoing crisis: human pressure leading to unprecedented environmental degradation, climatic change, social inequality and other negative planet-wide consequences. This crisis stems from a dramatic increase in human appropriation of natural resources to keep pace with rapid population growth, dietary shifts toward higher consumption of animal products and higher demand for energy. There is an increased recognition that Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are linked to one another, and priorities such as food production, biodiversity conservation and climate change mitigation cannot be considered in isolation.

The landscapes of West Texas, like much of the western United States, are iconic — home to working cowboys, open spaces and some of the most intact landscapes remaining on the North American continent. As domestic and international energy usage continues to rise, this region has become the center for America’s energy future. At the same time, will local communities have a say in the fate of their land?

Texas is the only energy-producing state without systematic laws, regulations or incentives to protect land resources and surface owners from damages caused by energy development.

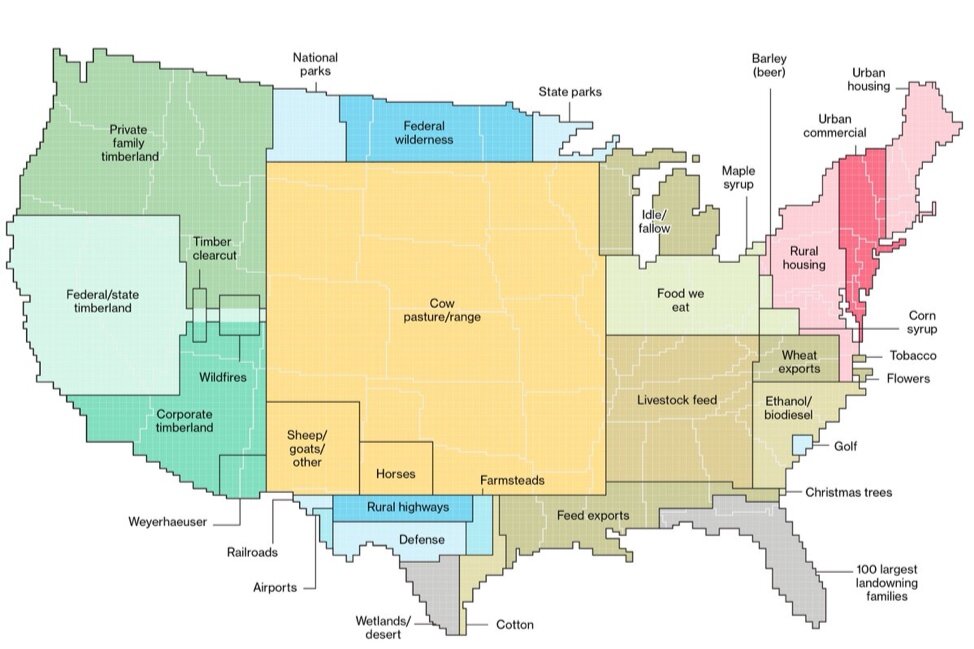

A recent Bloomberg article (Here’s How America Uses Its Land) broke down how the United States is carving up the 1.9 billion-acre land mass of 48 contiguous states into a collage of cities, farms, forests, and pastures that we use to feed ourselves, and create value for business and recreational use.

In a so-called post-truth era, we are actually collecting more data on a wider variety of factors than ever before. These data sources can—and should—help us to make better decisions on a range of comprehensive issues.

The list of words describing Mitchell is lengthy — oilman, philanthropist, developer, sustainability pioneer, environmentalist, entrepreneur, futurist, Renaissance man, visionary. Some of the labels seem contradictory because Mitchell was a man of incongruous passions.

If Texas were a sovereign country, it would rank as the tenth largest economy in the world, with a GDP of $1.7 trillion. Texas also ranks highest among states in the United States for business. In fact, Texas has added 350,000 jobs in the past year (one in seven new jobs in the U.S. were in Texas). Texas’ strong economy is married to the current energy boom in Texas. Major oil and gas formations in Texas include the Barnett, Eagle Ford, Haynesville, and Permian Basin. The Permian Basin alone is projected to exceed Saudi Arabia in production by 2023.

Texas continues to grow and prosper for many reasons and, as Texans, we should be forever thankful. We tend to possess an old-fashioned work ethic that marries friendilness, diligence, and a unique adaptibility. We have a favorable tax structure and a prudent, although sometimes lenient, regulatory environment; a pleasantly warm climate most of the year; and vast, magnificent topography and ecoregions, from the East Texas Pineywoods, Gulf Coast waters, and farmlands of the Rio Grande Valley to the windswept high plains of the Texas Panhandle and rugged moutains and biodiverse deserts of West Texas.

The Trans Pecos region of West Texas is a state treasure. It is in the Chihuahuan Desert, the most biologically diverse desert ecosystem in the Western Hemisphere, home to hundreds of species of birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and plants. Its vast, dramatic landscapes define Texas for Texas residents and visitors alike: the majestic mountains of the state’s two national parks, the immense, dark skies over the open plains, and the miles and miles of unfenced, undeveloped wild spaces.

Notwithstanding soft oil and gas prices, the Texas energy industry is booming. Nowhere is this more evident than in the West Texas Permian Basin. This dramatic growth has not only meant more oil wells but also an expansion of drilling closer to the ecologically sensitive Trans Pecos/Davis Mountains region.

Land. It’s what drew settlers to Texas—the promise of unlimited wide open spaces. Those vast untamed expanses gave birth to the rugged individualism that later wrestled Texas away from Mexico and helped create an independent country. As nationhood gave way to United States statehood and on into the 21st century, land continues to define both Texas and Texans today.

Restoration of native plants and habitat in tandem with energy sprawl could be a bridge to a better future for residents, communities, and the general landscape of the greater Big Bend region of the Trans-Pecos area of West Texas.

Since 1932, McDonald Observatory has enjoyed nighttime skies as dark as any major astronomical observatory in the world. Its remote location, in the heart of the Davis Mountains of West Texas, seemed to ensure this for decades to come. With the boom in oil and gas related activities in and around the Permian Basin, and now in the greater Big Bend region, the past ten years has seen a gradual brightening, low, along the Observatory’s northern horizon.

The iconography of Texas centers in fierce independence and rugged individualism. The Battle of the Alamo, early Texas Ranger companies patrolling the frontier, and cowboys wrangling vast cattle herds all come to mind.

Texas has a unique history in which many are familiar although don’t necessarily link with a number of today’s most important conservation issues.

The Nature Conservancy states that the largest loss of open space is now caused by energy sprawl—the amount of land resources developed for the production of energy from both fossil and renewable resources and all of the associated infrastructure. Nowhere is this phenomenon more apparent than the Big Bend or Trans-Pecos region of West Texas.