AIR & WATER

Air and water are natural resources under pressure from energy development in the Big Bend region, and both are essential for not only residents but also the wide array of plant and animal species in the region. This page includes a variety of news stories, scientific resources and opinion pieces on air and water.

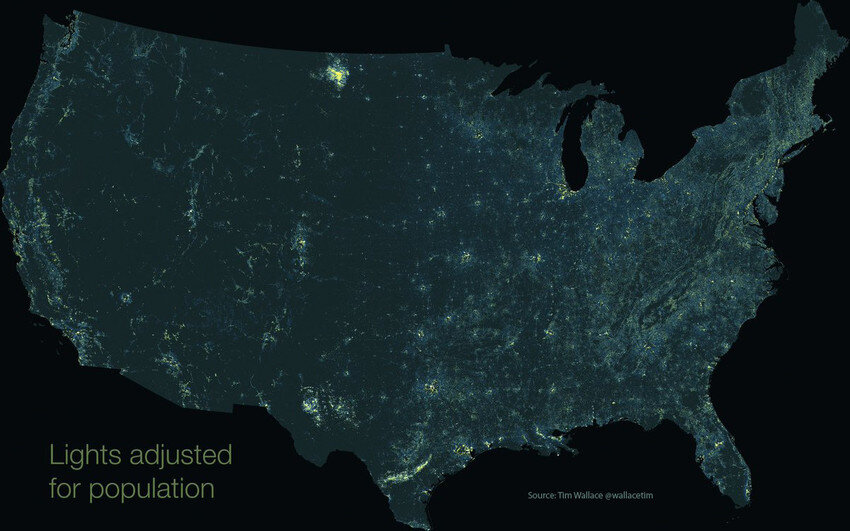

The map was created by subtracting population from light output, which highlights areas that throw off more light than predicted given their population density. It isn’t the glowing metropolitan centers of New York and Los Angeles that stand out, but regions like the oil-rich corner of South Dakota or the final leg of the Mississippi River. Some of the most prominent patterns on the map appear in regions where shale oil is being extracted.

McDonald Observatory is collaborating with local communities and businesses, including the oil and gas industry, to promote better nighttime lighting, i.e., cost efficiency, improved visibility & safety, and dark skies for the Observatory.

Diana Nguyen speaks to Bill Wren of McDonald Observatory, whose job is to keep the skies of Far West Texas dark. They discuss Wren’s collaboration with oil and gas companies and municipalities across the region, and what residents can do to help.

Turbines would use excess gas from drilling sites to power fracking equipment.

If light bulbs have a dark side, it’s that they have stolen the night. The excess light we dump into our environments is endangering ecosystems by harming animals whose life cycles depend on dark. We’re endangering ourselves by altering the biochemical rhythms that normally ebb and flow with natural light levels.

In a so-called post-truth era, we are actually collecting more data on a wider variety of factors than ever before. These data sources can—and should—help us to make better decisions on a range of comprehensive issues.

This map called Earth at Night, Mountains of Light was developed by cartographer Jacob Wasilkowski using NASA satellite imagery to map the world according to nighttime brightness.

If you check out West Texas, you might notice the light peaks don’t necessarily correspond to cities — some of those are oil fields where natural gas is flared to dispose of it.

In West Texas, an oil boom is creating a major problem for producers and locals alike: wasting natural gas by burning or flaring it, which sends billions of cubic feet of CO2 into the atmosphere. Not only does the flaring cost the industry money, but the release of gases damages the climate and could be toxic to those living near the fracking rigs dotting Texas oil fields.

Wilson’s camera can reveal plumes of smoke pouring into the air, though the camera can’t tell the difference between say, steam or toxic chemicals. But, Wilson is pretty sure what she’s seeing is pollution. “If you’re seeing something and it’s coming from the equipment on an oil and gas site then the gases are most likely going to be hydrocarbons. No matter what the industry tries to tell us. It certainly not cotton candy.”

Houston oil company Apache Corp. has doubled a gift to help save a revered West Texas swimming hole.

In addition to donating $1 million to repair the shuttered Balmorhea State Park Pool, the company has donated an additional $1 million to create an endowment to preserve and support the iconic West Texas state park.

West Texas is famed worldwide for its vast crude oil reserves. But for more than 75 years, a small patch of the Permian Basin has also been valued for its pitch-black night sky. Those two prized natural resources have clashed in recent years as oil drilling has brightened the sky near the McDonald Observatory.

Notwithstanding soft oil and gas prices, the Texas energy industry is booming. Nowhere is this more evident than in the West Texas Permian Basin. This dramatic growth has not only meant more oil wells but also an expansion of drilling closer to the ecologically sensitive Trans Pecos/Davis Mountains region.

The loss of darkness can harm individual organisms and perturb interspecies interactions, potentially causing lasting damage to life on our planet.

Since 1932, McDonald Observatory has enjoyed nighttime skies as dark as any major astronomical observatory in the world. Its remote location, in the heart of the Davis Mountains of West Texas, seemed to ensure this for decades to come. With the boom in oil and gas related activities in and around the Permian Basin, and now in the greater Big Bend region, the past ten years has seen a gradual brightening, low, along the Observatory’s northern horizon.

The Nature Conservancy states that the largest loss of open space is now caused by energy sprawl—the amount of land resources developed for the production of energy from both fossil and renewable resources and all of the associated infrastructure. Nowhere is this phenomenon more apparent than the Big Bend or Trans-Pecos region of West Texas.

McDonald Observatory has partnered with oil and gas organizations to protect the dark West Texas skies. This video details the issue of light pollution caused by oil and gas activities in the Permian Basin and their potential to effect the observatory's ability to study the cosmos.

The video also outlines solutions that are documented in an agreement for Recommended Lighting Practices for oilfield activity that has been published by the partnership of McDonald, the Permian Basin Petroleum Association and the Texas Oil and Gas Association. This project was made possible by a grant from Apache Corporation.

In arid West Texas, where rain is infrequent and rivers and lakes are few, groundwater – water from sources beneath the surface of the earth – is key to survival. And as the oil and gas industry in the Permian Basin demands more of this resource from the surrounding area, researchers are scrambling to study the systems of webbed aquifers that feed households, farms, ranches and industry in the region.

But for residents there’s a familiar tension over who gets to decide the fate of their water.

PBPA gets behind an idea that is out of this world: the Dark Skies Initiative. Acting before drilling operations pose a serious problem in Reeves County and Jeff Davis County (and the Fort Davis area), oil companies get on board a plan to keep the skies dark above the McDonald Observatory.

The University of Texas’ McDonald Observatory in the Davis Mountains in West Texas is one of the darkest spots in the continental United States. Lights from the Permian Basin oilfield to the north, the center of U.S. oil and gas activity, are creeping closer to the 85-year-old observatory, home to one of the world’s largest optical instruments. The sate’s oil and gas regulator issued nearly 11,000 drilling permits in the Permian Basin in 2014.