Private Property Rights Matter For Collective Conservation

The iconography of Texas centers in fierce independence and rugged individualism. The Battle of the Alamo, early Texas Ranger companies patrolling the frontier, and cowboys wrangling vast cattle herds all come to mind.

Texas has a unique history in which many are familiar although don’t necessarily link with a number of today’s most important conservation issues.

The Republic of Texas was a sovereign nation (1836-1845) until it was annexed by the United States. At the time of annexation, Texas retained what remained of its public land, which was then sold to retire debts from years of war or offered as homesteads to entice settlement of the far western regions of the state. These actions helped form a state whose open spaces are more than 95 percent privately held. This fact, in turn, has created immeasurable impact on our culture and identity, which influences unique challenges for the conservation of these lands.

As Texas’s economy evolves, demographics shift and agricultural practices become more efficient, our state’s residents continue to gravitate to urban areas. Today, the state’s population is approximately 85 percent urban. Meanwhile, the rural lands of Texas account for more than 80 percent of our state’s land mass. Alarmingly, those lands are owned by less than 1 percent of residents. This electoral imbalance reveals an inherent threat to natural resource conservation in our beloved Lone Star State.

Land stewards cultivate key societal, natural resource benefits

There is no clearer illustration of this imbalance than the fact that there are more state representatives and state senators in the greater Houston area than there are west of Interstate Highway 35 (which runs north and south from Laredo, San Antonio, Austin, Waco, Dallas/Ft. Worth metroplex and the border with Oklahoma). Simply put, the urban areas have the votes and the rural areas have the natural resources. These private, rural lands are where rainfall recharges our aquifers, where our air is filtered, where carbon is sequestered, where our wildlife lives and where a great deal of our food and fiber is grown.

It may sound counterintuitive; however, the private property rights of our rural landowners result in significant societal and natural resource benefits. Property rights are not only fundamental to liberty, but, more to the point, serve as a powerful motivator for land conservation. An owner of a tract of land has a vested interest in being a good steward of it. Erode those property rights, and the motivation to steward the land, and related ability to protect it, begin to soften.

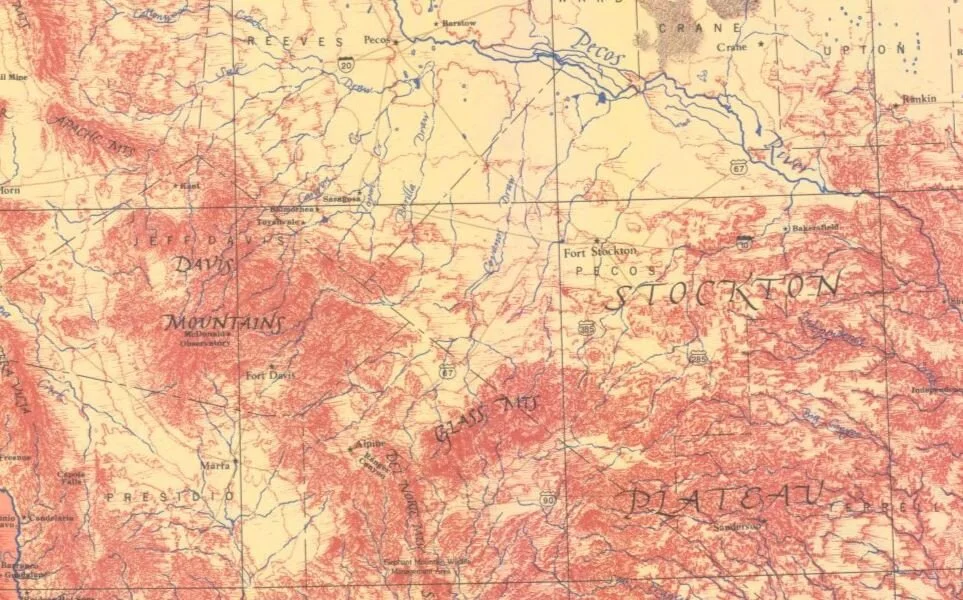

Eminent Domain, Private Property Rights in the Trans-Pecos

Nowhere are the private property rights of rural landowners more assaulted than under current eminent domain statutes. Energy exploration, development, and transportation are primary economic drivers for the state of Texas, especially in the Trans-Pecos region of West Texas. Pipelines and transmission lines power our state, literally. However, those lines cross a lot of private land between the well or plant and the gas pump or light switch. As a “common carrier,” the builders and operators of these lines are afforded the awesome power of eminent domain. This fact, alone, clouds any negotiations between a pipeline builder and the landowner that sits in their planned path.

When a “common carrier” approaches a landowner with an offer of money for needed land, the landowner knows that they can accept the offer, or be sued and still lose the land in question. The only question to answer with litigation is how much money exchanges hands. That total is unknown and further complicated by the unknown cost of litigation (e.g., legal fees, expert witnesses, court costs) which can oftentimes grind along for years.

Adding insult to injury, current statute forbids landowners from recovering attorney fees from the condemner if the court finds in their favor. Should a land transaction like this go into condemnation and litigation, the absolute most a condemner will pay is a fair market value for the land. The absolute most a landowner will ever receive is the fair market value of their land, less the cost to defend their estate. The landowner will never, ever be made whole.

Let that sink in.

Advocating for Private Land Owners, Land Conversation

Someone gets drug into a legal fight against their will to defend what is theirs and, in the end, they still lose that land along with whatever legal expense they incur. Commonsense and common decency demands better.

The statute should be designed to incentivize common carriers by stick or carrot to make reasonable offers on the front-end of negotiations with the landowner. Fair monetary compensation allows landowners to mitigate damages to the remainder of their land, or to replace the lost acreage. Fair treatment of landowners on placement of lines and the construction process itself attenuates the ecological impacts of the project.

As Texans, we are dependent on a small cadre of land stewards for our clean air, clean water, healthy wildlife populations, and the beautiful open spaces that we love. I believe we owe them a debt of gratitude and need to help support and advocate for their ability to keep those lands intact.